About Phyllis

Phyllis Kenner Robinson, “the first lady of Madison Avenue’s creative revolution,” as she was dubbed by the Financial Times following her death, was a pioneer in every sense of the word.

When Doyle Dane Bernbach opened its doors June 1, 1949, Phyllis joined as Copy Chief, the first female copy chief in U.S. history. “Copy chief of me,” she would later joke, as she was also the only writer Bernbach employed. Phyllis often downplayed her role as a female trailblazer and was always quick to praise the women, like Bernice FitzGibbon and Margaret Fishback, who had inspired her. Yet it was Phyllis who paved the way for women to break out of traditional creative roles in food and fashion divisions. And she then went on to help build the most creative and diverse agency of the Mad Men era, which broke all the rules for both men and women alike.

Phyllis was born in New York City on October 22, 1921. From a young age, she had an interest in advertising, inspired by the ads she read out of her Third Avenue apartment window and the roadside signs for Burma Shave she loved seeing while taking drives with her father. She developed an interest in politics and majored in sociology at Barnard College graduating in 1942. Her first job was with the Federal Public Housing Authority in New York. In 1944, she married Richard Robinson, who was soon drafted. For two years, she followed him from post to post across the country, working six different jobs, including a few in advertising. In 1947, the couple returned to New York, and Phyllis began working in sales promotions at Grey, where Bill Bernbach was then Copy Chief.

No one considered Phyllis good enough to work on national campaigns—no one, that is, except Bernbach. He recognized Phyllis’s talent and had her transferred to his department. Two years later, Bernbach asked Phyllis to come along when he founded his new agency with Ned Doyle and Maxwell Dane.

“Of course we didn’t really have the great sense of pioneering that we have in retrospect. It was more like kids being let out of school,” Phyllis told a Japanese interviewer in 1971. “We felt free and sprung. Perhaps I should correct myself. I say we didn’t have a sense of pioneering, only because that sounds a little pompous and we didn’t feel pompous at all. We just felt free, as if we had broken our shackles, had gotten out of jail, and were free to work the way we wanted to work.”

Phyllis continued to partner with then Head of Art, Bob Gage, who also joined the new agency from Grey. At DDB, they perfected Bernbach’s “creative team” concept and forever changed the way the industry made ads. And Phyllis went on to develop her witty, conversational writing style that became a hallmark of DDB’s early work for clients like Ohrbach’s and Polaroid.

For Phyllis, this newfound freedom came with tremendous responsibility. The work didn’t just need to be creative; it had to do the job for the client as effectively as possible. “That means distinguishing between an untried idea that’s good and an untried idea that doesn’t deserve to be tried,” she wrote. “And it means being tough on the good ads too. Throwing out a good idea when you think it’s possible to come up with a better one.”

As DDB grew, Phyllis was charged with hiring and training a growing department of creatives. At first she only hired women but quickly realized she found it just as easy to supervise men. Phyllis was promoted to vice president in 1956 and as her creative staff developed, it became about 50% male and 50% female. The real challenge was finding the right kind of talent—understanding that the usual standards for hiring creatives wouldn’t work.

Phyllis was free to set her own rules

and fostered an atmosphere where any idea, no matter how wild or foreign it seemed, was welcomed and considered by the agency. And the same could be said of its talent, many of whom were traditionally overlooked or unwelcome in the WASP cultures of most agencies at the time.

“An important part of my personal style of direction and teaching was to encourage everyone in his own idiom, in his own personal way of doing things,” Phyllis said. “There would be no point in having many, many little Bill Bernbachs and Phyllis Robinsons, a sort of assembly line product. Instead we have all these wonderful strains of all these people intermingling.”

Indeed, some of the most notable names in the industry were among the ranks: Bob Levenson, Helmut Krone, Julian Koenig, Mary Wells Lawrence, Roy Grace, Rita Selden, George Lois and the list goes on and on. Many would leave or start their own agencies, and many would return.

“They have encouraged diversity. It is a very unique place because the people who run this place are unique,” said Paula Green, most know for her Avis We’re #2 campaign. “Atmosphere does not percolate from the bottom up. It comes from the top down. You can only be as good as the people up top let you be.”

Lore Parker, another of DDB’s famed copywriters, summed up the atmosphere best: “We have a very serious writer who was an electronic engineer before we hired him. And another one who was a bartender. We have a Pop-Mod-Beatnik art director with long frizzy hair and purple velvet jacket. We have a woman writer who’s the sensible mother of four children, and another one who’s a swinging chick with mile-long eyelashes and skirts way above her knees. We have Jews and Italians and Irish and Anglo-Saxons. We have kids right out of school and mature men in their late forties. The only thing we all share is ability—and a healthy respect for each other’s work.”

It was this environment of respect that Phyllis nurtured and found most important. Respect for coworker, client, the audience and yourself were the secrets to success she shared in her acceptance speech to the Copywriters Hall of Fame at her induction in 1968.

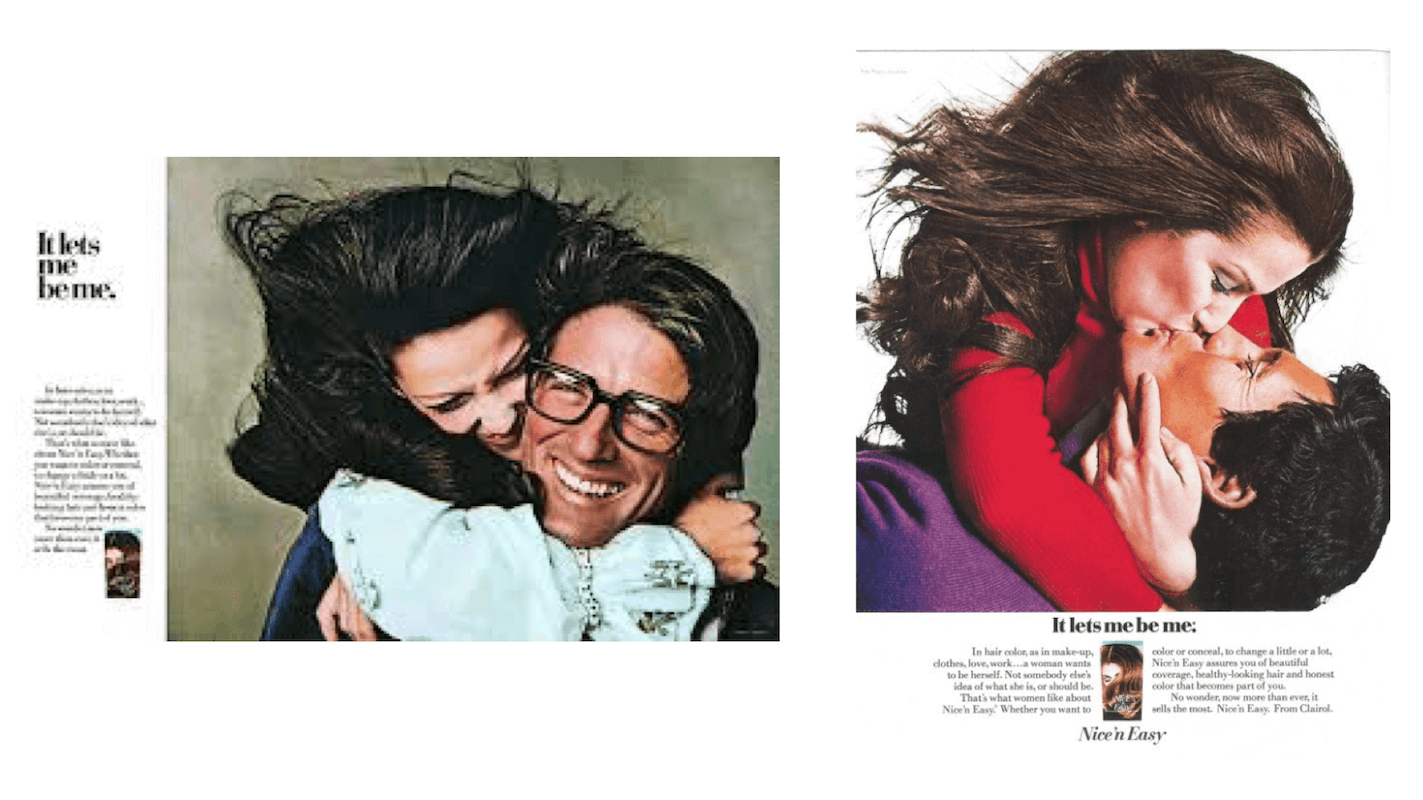

In 1962, when Phyllis became pregnant with her first child, she stepped down from her role as Copy Chief and began working a three-day week. “I walked into Bill Bernbach’s office and told him what I wanted. He cried a little, but he said okay,” Phyllis told DDB News in 1966. Some accounts say it took a little more persuading. Either way, Phyllis’s talent won out and she continued to run the legendary Polaroid account and work on Clairol products, for which she helped define the entire “Me” generation with her liberating “It let’s me be me” campaign. She was also involved in many public service efforts, including the creative review board of the Media Advertising Partnership for a Drug-Free America, and was a founding member of Ads Against AIDS.

Phyllis retired from DDB in 1982, but continued to consult with the agency throughout the 1990s. As summed up by Keith Reinhard, DDB Worldwide’s Chairman Emeritus, who in 1986 co-orchestrated the agency merger that formed Omnicom and preserved the DDB legacy for future generations: “As I got to know her better I realized that, as Bill Bernbach’s first copy chief, Phyllis set the tone for the creative culture we so cherish at DDB.”

Phyllis Robinson died on December 31, 2010 at the age of 89. We are proud to launch the Phyllis Project as a tribute to her vision, intelligence and trailblazing contributions to our industry.